While U.S. President Donald Trump’s threat to impose 25% tariffs on both Mexico and Canada was kicked down the road to Feb. 1, our North America Coface Economist Marcos Carias lays out his thoughts on the likeliest scenario for a looming trade war.

UPDATED at 3:08 p.m. EST, Feb. 11, 2025: On Feb. 3, President Trump agreed to pause the 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico for 30 days after the Canadian and Mexican governments promised to address concerns on border security and drug trafficking. While the extension bought some additional time for the U.S.’s neighbors to the north and south, it still leaves the global economy uncertain about whether a trade war crisis was averted.

Amidst the deluge of executive orders issued by President Trump on Inauguration day, the flagship and much anticipated topic of tariffs was conspicuous for its absence. Instead, the newly sworn in head of the executive branch punted action in this arena to Feb. 1. As always, taking him “seriously but not literally” in this context means preparing for some form of consequential measures, while knowing the administration is never married to any particular set of policy details. And yet, from the talk we’ve been hearing consistently since the election, Canada’s looking like a strong contender to be first in the line of fire. While both North American neighbors have been the object of tariff threats, Mexico seems better positioned to avoid or at least mitigate them.

First, Mexico has more to offer in terms of concessions, and therefore, may have more to leverage. The central role played by Mexico in migration and drug trafficking means that effective cooperation can actually make a noticeable dent in these issues, stateside. Second, there is room to build a functional relationship between Trump and Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum. Though they might appear distant on the left-right spectrum, there are points of overlap between Trumpism and Morenismo, including the belief in a strong executive branch, critiques of the media and traditional elites, and the idea that political leaders should assertively put their country first.

By contrast, there is genuinely no love lost between Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. And though the PM will be soon replaced, the Liberal Party of Canada is an avatar of the specific strain of progressivism Trump repudiates when enacting diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) rollbacks. While Sheinbaum has so far referenced retaliatory tariffs vaguely and as a weapon of last resort, the detail and severity of Trudeau’s counter-threats signal resolve (and maybe a whiff of resignation). A swift blow to the Canadian economy during the Liberal party’s last few months in power can also stack the deck even further in favor of Pierre Poilievre and the Conservative Party in the upcoming elections.

With this in mind, it is worth saying a few words on the kinds of tariffs that would make the most sense for the U.S. to enact, based on my reading of the incentive landscape and the structure of both economies:

- In terms of schedule, it is likely that whatever tariffs get introduced will be phased-in over time, building up to their announced rate gradually across several years, with each increment acting as a potential incentive lever to extract concessions.

- In terms of intensity, there is a precedent in Trump’s first term of watering down tariff rates, which are seen either as initial negotiation terms or signaling tools.

- In terms of product coverage, we’re unlikely to see indiscriminate tariffs.

Expect precision strikes, not blanket tariffs

So, what industries will bear the brunt of these decisions? Let’s start with the two heavyweights.

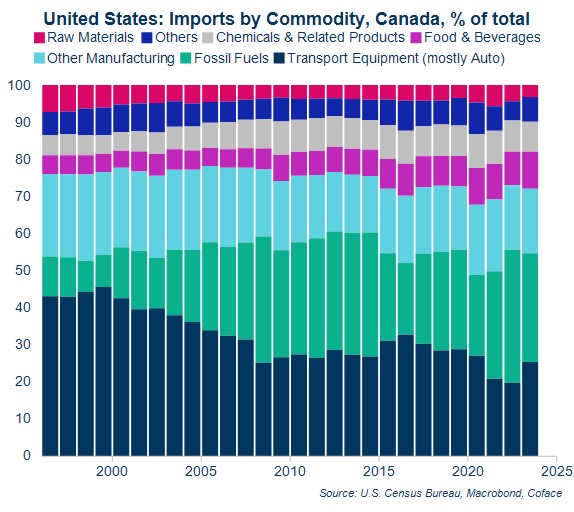

- Oil & Gas: With U.S. inflation threatening to start rising again, the Trump administration will be particularly sensitive to anything that might push up energy prices. Canada is the main exporter of fossil fuels to the U.S., accounting for around half of U.S. imports. The U.S. could theoretically diversify import dependence by trading more with OPEC countries, but that could create more potential geopolitical exposure. However, the U.S. and Canada share a vast and integrated pipeline network, including major pipelines like Keystone and Enbridge’s systems, making Canadian oil and gas easily accessible and cost-effective. Canada's proximity ensures lower transportation costs compared to imports from distant countries, especially for landlocked refineries in the U.S. Midwest that heavily rely on Canadian crude. Furthermore, many U.S. refineries, particularly along the Gulf Coast, are designed to process heavy crude oil, which Canada supplies in abundance. Reconfiguring these refineries to process lighter crude from other sources would be costly and time-consuming.

- Automotive: Again, an important dependence for the U.S., with imports from Canada accounting for 15% of all American imports in the sector. Here, the political incentive is not so much inflation (car prices matter, but not like gas prices), but rather the Automotive industry itself, which is a key employer, considered geostrategic, and has a powerful symbolic significance. Again, diversification would be very complicated. Many auto parts cross the U.S.-Canada border multiple times during the manufacturing process. Replacing this seamless supply chain with other sources would require a complete restructuring of production networks.Canada is investing in electric vehicle battery production and has access to critical minerals like lithium, nickel, and cobalt, which are crucial for the EV transition. There is an argument that tariffs can encourage re-shoring of production capacity, but if this is the goal then there is an even greater incentive to back-load the tariff schedule. This would create an additional incentive to get assets out of Canada sooner, rather than later.

Already with these two sectors, we’re talking about roughly half of Canadian exports to the U.S., there are strong incentives for negotiating carve-outs. If I try to guess a likelier target for stronger tariffs, the agrifood industry comes to mind. There is a longstanding dispute in the dairy market, where Canada applies tariff-rate quotas that the U.S. has criticized as detrimental to U.S. farmers and food manufacturers. Other countries applying protectionist practices on the U.S. is very important for Trump, and “buying American” is one of the most important gestures he expects in return for his favor. Removing the Canadian exception on steel and aluminum tariffs is another obvious way to go.

Though trade peace is still possible, it’s not all that likely

Many are wondering what concessions could placate Team Trump. Stricter rules of origin on automobiles and auto components to reduce supply-chain dependence on China will be a likely demand, and of course refraining from retaliatory tariffs. We’d also expect that the Trump administration would want to wait until Canada’s current leadership crisis gets resolved before any hard moves, especially considering the Conservative Party’s likely rise to power. After elections (likely in spring, October at the latest), the USMCA Agreement review/renegotiation will be just around the corner, providing a natural framework for trade bargaining to take place.

Our baseline (i.e. likeliest) scenario is therefore not a 25% blanket and front-loaded tariffs. We could have tariffs on some specific products going as high as 25% (easy to enact for steel and aluminum), lower tariffs on goods that are important for the Canadian economy but not super-critical for the U.S. (see: food products, lumber, chemicals including fertilizers, machinery and other manufactured goods), and carve-outs on critical minerals, energy, and possibly automotive; all of which can be back-loaded. This would be enough to arrest the ongoing recovery and flip the economy into recession. Previous simulations of 10% blanket tariffs scenarios yielded GDP losses on the order of 2-3% (assuming tariffs to be essentially front-loaded, though).

All of this being said, it is not impossible that Team Trump will want to send a strong message early on to gain psychological leverage on bigger fish like China, Mexico and the European Union. Being severe on what is arguably the U.S.’s closest ally (and an important business partner) would achieve that. The reservoir of political capital is the strongest at the beginning of the term, and the continued resilience of the U.S. economy might embolden Trump to think that the country can take the hit of making an example out of Canada. If we inch closer to 25% tariffs being the rule rather than the exception, we’d be looking at GDP losses on the order of 4-6%, which is around what we had in 2020. Again, possible, but not the likelier scenario.

In any case, Canadian businesses should be prepared to buckle up.

Marcos Carias is a Coface economist for the North America region. He has a PhD in Economics from the University of Bordeaux in France, and provides frequent country risk monitoring and macroeconomic forecasts for the U.S., Canada and Mexico. For more economic insights, follow Marcos on LinkedIn.

Are you doing business with Canadian companies and want more predictive insights? Contact our experts now.